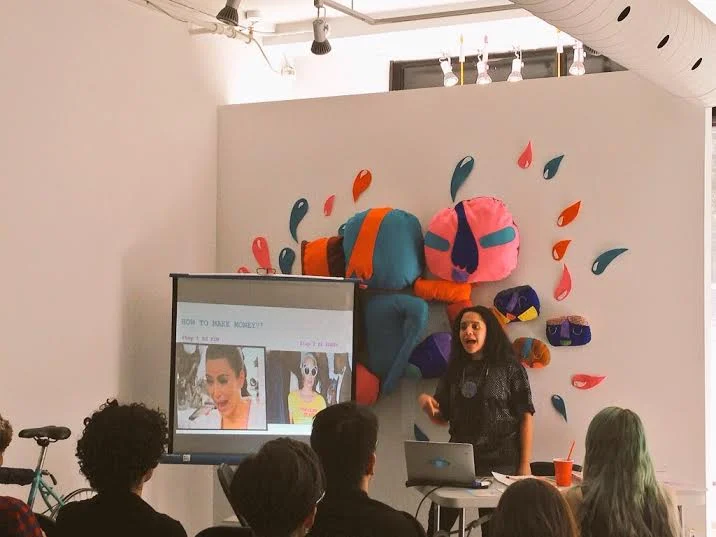

Guests seated in the pews of St. George the Martyr church at the Music Gallery last Saturday night were gifted with an education in Toronto hip-hop history and granted insight to the struggles black women artists face gaining and sustaining success in the creative industries in the contemporary moment.

Moderator Alanna Stuart (Bonjay, CBC) joined Ayo Leilani (Witch Prophet, co-founder of 88 Days of Fortune), Val-Inc, Amanda Parris (CBC) and Garvia Bailey (JazzFM) for a lively and compassionate panel discussion.

“We were starting the panel back there,” Stuart joked as the five women took the stage already smiling and chatting with each other.

The central topic shifted almost immediately from “the new black” to the meaning of being “more black.”

“Being more black is being proud, being more visible,” Leilani offered, “being unapologetic.” She cited Shabazz Palaces, THEESatisfaction and Norvis Junior as artists whose politics have set the stage for people like Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar today.

Responding to Stuart’s question, “Are you ‘more black?’” Val-Inc explained, “It’s a different context, coming from Haïti,” where the cultural connection to Africa is felt more strongly.

Returning to ideas of pride and visibility, Leilani critiqued the lack of support for Frank Ocean since his coming out as bisexual. “I challenge stereotypes,” she offered, “because I’m a queer woman of colour in the hip hop scene.”

The tone of solidarity was maintained throughout the evening. Stuart got laughs from Bailey and Parris after asking if the broadcasters ever felt “boxed in,” and quickly changed her question to “how have you felt boxed in?”

“Now is a good time, because people are realising,” Bailey said, “but I struggled.” Comparing the CBC to a giant, slow-moving iceberg, she said her strategy for surviving and making change within the institution was to approach her work there like she was, “in it, but not of it.”

Parris, newer to the job, validated the battles Bailey had to win to attain the position and visibility in the media industry that she now has. “Thank you for paving the way for me,” she said.

After translating Stuart’s description of her from “experienced” to “oldest person on the panel,” Bailey took the lead on recognizing the Toronto hip-hop trailblazers that helped shape her ideas of how black music and musicians could be: Dream Warriors, Michie Mee, Women Ah Run Tings. Their innovation was out of pure necessity said Bailey, out of feeling like, “I may never be on this stage again.”

Parris quickly picked up on this, arguing for the development of systems and spaces to document and archive the work of black artists. “We’re so bad at remembering our history,” she said, pointing towards young artists today who feel like they’ve got to re-invent the wheel, not knowing of the work that was done before them.

That the panellists were personally familiar with the toll this type of labour can take was evident. “Taking a moment for self-health is really important,” Leilani urged. She referenced her relationship with 88 Days of Fortune and how she sometimes felt pushed into a maternal role in her creative community, a position that strips her of her right to be human and angry. “I’m invisible while this thing is visible,” she said.

Stuart spoke to the privilege of living and working in a major urban environment and asked what could be done to support young artists growing up in places with fewer resources.

Saying that she’d recently seen some videos coming out of the Jane and Finch rap scene, Leilani praised the time, talent and energy that young people were putting into their art. “These kids are doing it themselves,” she said, spurring a “preach!” from a member of the crowd.

The audience clearly felt a hunger too. Much of the Q&A period centered on grants – who allocates them, how to get an edge over other applications, and, most poignantly, how to get past the shame of asking other people for money.

Crediting Kanye West for helping her develop a “hip-hop mentality of entitlement,” Parris emphasized the importance of confidence. “Those people are not giving you charity,” she said, “they are making an investment. You have to walk in knowing you are a gift to them.”